Geopolitics, Digital Sovereignty…What’s in a Word?

Abstract: An overlay of digital networks and services often operated by global players encircles and “shrinks” the planet. At the same time, the geo-political dynamics have entered a cycle of feud for leadership between trade blocs who compete for economic and industrial leadership but also on ethics, values and political outlook. In this context, governments and lawmakers are struggling to combine the need for global cooperation in digital matters with the imperative to protect their jurisdiction from undue influence and provide economic agents with the means to compete on a global scale. The concept of “digital sovereignty” was carved to address this. Words matter a lot especially when they are meant to translate political goals. We argue that “digital sovereignty” lacks meaning and teeth, whilst the concept of “strategic autonomy” is more operative, contains in itself the elements of strategic planning and should lead EU to aim at genuine “digital non-alignment”.

The context

The paradox

Nations (and groupings thereof), industry and international organizations have spent megabillions in the last decades to connect the globe. Sub-marine cables, satellite communications, fixed and mobile networks, the Internet, enabled global connectivity and access in the most remote places.

To enable this, the geo-political dynamics shaped a world of multi-lateral collaboration, with the WTO1 as the arbiter of a frictionless global trade. The global village was not a rose garden indeed, but multi-lateral regulatory cooperation would fix it and global trade would make the world a safer and wealthier place for all. So was the narrative for example when China became a member of the WTO in 2001.

Fast forward to 2021, “second life” has become our life, digital connectivity has infused through the economy and society worldwide, M-Turks from Nigeria or India work in real time for Silicon Valley corporations, geography is ended (so is privacy, but this is a different subject). And yet, as technology, economics and politics have shaped this global cyber-reality, globalization is challenged by the (re)formation of more or less antagonistic trade blocs. After three decades of moving towards a single global market governed by the rules of the WTO, the international order has undergone a fundamental change and an open, unified, global market may indeed become a thing of the past (Fischer, 2019).

It’s more than the economy, you know

With different narratives, each regional trading bloc is developing its own roadmap to achieve global digital success-and indeed global supremacy. Be it President Biden signing an executive order strengthening the “Buy American” provisions, China asserting its primacy in digital matters and global trade, India promoting a techno-nationalistic agenda or Russia developing its offensive cyber capabilities, it is as if global trade in the 21st century was bound to be a discordant zero sum game.

What’s more, this global competition in not only industrial, technological or economic but also about visions, values and methods. Whether trade irritants can dissolve in good intentions remains to be seen2.

In a conference of the Centre for Economic and Policy Research in February 2021, Dr Christian Bluth3 argued that the most important challenge for EU today was the increasingly charged geopolitics of trade. He argued that trade policy is increasingly used for projecting power rather than generating prosperity, and several countries are “weaponizing” the trade dependence that others have on them.

Europe, how many divisions?

Be it for tea in China, spices from the Malabar Coast, gold in South America, coffee or rubber in Africa, oil in the Middle East, Europe did not have a problem with global supply chains or national sovereignty when it was dominant in worldwide trade and industry. It even got support from moral or political authorities (Treaty of Tordesillas in 14944, Berlin Conference, 18855) and carved the political concepts to lean on, e.g. Westphalian sovereignty. Today’s situation is indeed slightly different.

A Pacific centered *digital* world map

Once an economic giant (but a political dwarf), Europe’s ambitions for the “digital decade” are caught in between a duopoly with US and China dominating the global digital economy. The Old Continent appears to have already lost the artificial intelligence battle – to name but one. We need to wake up to the fact that we are falling behind in 5G development, and its application in service and industrial verticals, and so running the risk of becoming a minor player in the global contest 6.

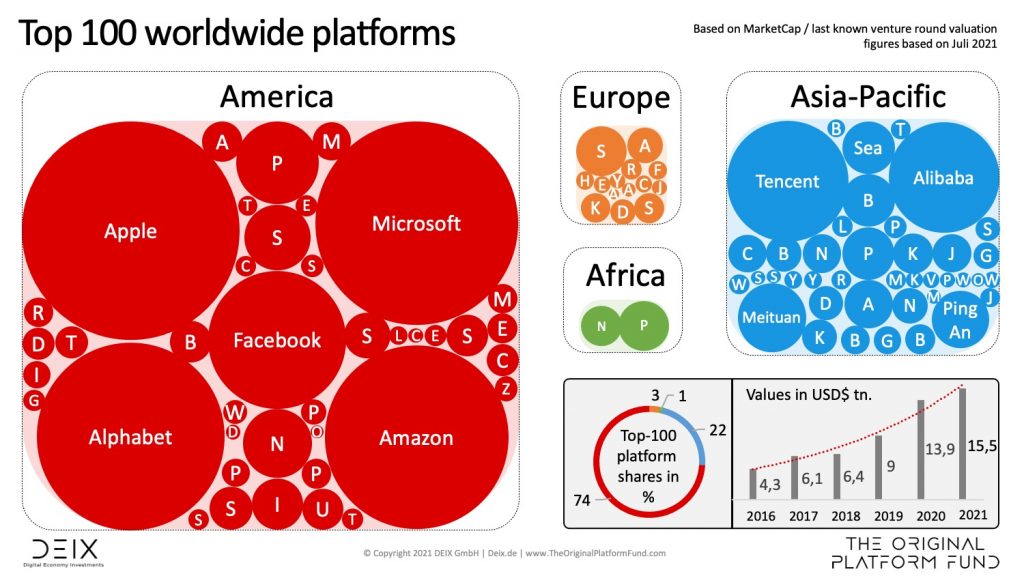

In the platform economy, nobody can hear EU scream

GAFAMs (a short for Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft) and BATs (Baidu, AliBaba, Tencent) are not only global platforms with revenues much larger than many countries’ GDP. They also integrate vertically and horizontally, absorbing potential competition, shaping the whole economy including for strategic sectors and the provision of public services. Incidentally, they also alter the fundamentals of the labor market. This market is not EU’s strong suit as shown in the following figure.

Digital sovereignty, a new concept to operate and compete in this context

Originating in the cybersecurity community, the concept of “digital sovereignty” gained ground in lawmaking circles with the increasing number of attacks on critical infrastructure (power, communications, water…), the global connectivity and the sky-rocketing number of IoT devices with its related security and privacy issues. The complex relationship with the previous US administration also contributed to propagate the idea that EU had to rely on its own capacity to defend itself in the hyper connected world.

Devising new fundaments to build EU policy in this challenging context, the European Commission -and some Member States – developed the concept of “digital sovereignty”, defined by Commissioner Breton8 as:

- Sovereignty on data, especially industrial data (a sovereign cloud)

- High performance computing and microchips

- Connectivity (5G, optical fibre and low orbit satellites)

With its Communication on 2030 Digital Compass issued in March 20219 the European Commission defined “the European way for the Digital Decade” to translate EU’s digital sovereignty objectives into specific targets. Additional policy instruments such as the Communications on Industrial Strategy10 specific the path towards EU leadership in digital.

Words matter-especially when they are meant to be performative

Digital and sovereignty, how does this add up?

The digitalization of the world adds a meta layer on top of the political authority. To set the rules of the game in its own jurisdiction, EU policy makers devised a series of regulatory measures: General Data Protection Regulation11, Cybersecurity Act, Directive on Network & Information Security12, Digital Services Act, Digital Market Act13.

The legal framework is set -and this is not trivial, but does it suffice to build EU’s capacity to be sovereign in the digital competition? Many EU companies that play in the global league are not particularly fervent of the concept of sovereignty as most of their operations and revenue are overseas. How about the indecision with Gaia-X14 constituency, or ARM (a British leading chip maker) acquired by its US rival NVIDIA (“a disaster for Cambridge, for the UK and for Europe” H. Hauser BBC Radio 4 in September 2020) and envisaging to subsidize a US company to build EU chip industry capacity?

Political and legal considerations

Defined by F.H Hinsley (1986, p. 1), sovereignty is « the idea that there is a final and absolute political authority in the political community […] and no final and absolute authority exists elsewhere” This implies, on the one hand, that no political authority can be half sovereign and, on the other hand, that the entity from which sovereignty emanates should be monolithic, or at least sufficiently integrated to project “final and absolute political authority”. Both characteristics are in contradiction with the way the EU is constructed and the breakdown of jurisdiction and competence between EU and Member States.

Does the exclusive competences of the EU15 grant EU lawmakers the means to walk the talk? What means sovereignty without jurisdiction? How sovereign when for example fifteen EU countries representing over 50% of the entire EU membership sign with China’s Belt & Road Initiative or European automotive brands ink deals with the GAFAs for data analytics, machine learning and artificial intelligence?

This might partly explain the bids from the European Commission to seize activities in areas the Treaties allot in principle to Member States, such as e.g. radio spectrum allocation, health or e-identity. Maybe “life on life’s terms” will change this breakdown of competence; for the time being, the EC’s bids have not been welcomed with open arms in EU capitals.

Where next?

Many assets to mobilize

EU may not be a leading player in several areas of the digital economy, e.g. platforms. Yet it has a series of assets to build on, such as

- The largest GPD in the world and a market of 500 million.

- Leadership in several domains (e.g. aeronautics, cryptography, banking, automotive retail)

- A very dynamic SME scene

- R&D and intellectual capital

- High end connectivity and networks (transport, energy, telecoms)

- Cultural diversity and a fundamental rights charter

Europe is a deep wellspring of talent, with a tremendous capacity to rebound, and a rare power of innovation: (…). Europe is also synonymous with actions and projects driven by exacting values and a commitment to positive and progressive construction16.

Strategic autonomy

We argue that leadership in digital does not mean leading in all segments of the tech industry, but rather the capacity to digitalize industry and services in a safe, secure and trustworthy way. With this come the questions of how to combine those assets, which battles to choose, which allogenous bricks can be part of the plan, who to partner with on what terms etc.

In other words, select strategic sectors and within those, make one’s own rules and own plans on its own terms. Strategic autonomy, literally, as in auto-nomos. This implies acting in several directions and selecting what to do and what NOT to do-which is often the forgotten part.

This is not new. To a large extent the EC (and several capitals) are headed in this direction with the recent Regulations mentioned above, the increased powers granted to ENISA17 in cybersecurity or the rules to participate in EU funded research projects.

Contrarily to the concept of digital sovereignty, the concept of strategic autonomy does not hint at any notion of protectionism, rather the idea that “you’re most welcome to operate in my jurisdiction as long as you play by the rules I set”. It also much more operational as it almost self contains the notion of a dynamic planning.

In a webinar of a Brussels Think tank in February 2021, Anthony Gardner, ex U.S. Ambassador to the EU said in a very poetic manner that “Digital sovereignty as sometimes heard in EU circles is chasing moonbeams”. Strategic autonomy on the contrary is very down to earth and operational.

Aim for the moon

In the debate on digital sovereignty -or strategic autonomy as we prefer to call it, China is the geo-political elephant in the room. In order to fight on the geo-political scene in a heavyweight (industrial) category, Europe often advocates to “partner with think-alike”, those who share EU values on freedom of speech, democracy and human rights. This makes sense, and is possibly much encouraged by the new US administration.

The other elephant in the tech and economic room are the GAFAMs. And as described earlier all EU trade partners ponder the ambition to be global leaders in the digital world-and act accordingly.

In this context, we argue that Europe could define a “third way”, a sort of “digital non-aligned” doctrine which would also give it total leeway to make its strategic choices and rules:

- Define areas for collaboration and no-go areas (e.g., in rexearch programs, in FDI).

- Keep friends close and enemies even closer (that’s what diplomacy is for)

- Respect historical allies whilst controlling lobbying and entry strategies

The continent has all it takes to embody this third way and build its own path in the otherwise digital bipolar world shaping before us. This might seem utopian but so was the European construction at its beginnings when the founding fathers launched the process in a devastated continent, which interestingly started with industrial cooperation on coal and steel, as essential to the economy then than digital is today.

Acknowledgement

This paper was written after a long discussion and exchange with a third person who prefers to remain anonymous.

1. The World Trade Organization is an intergovernmental organization which regulates international trade. The WTO officially commenced on 01/01/1995 under the Marrakesh Agreement, signed by 123 nations in 1994, replacing the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which commenced in 1948 (www.wto.org).

2. Some call for “differentiated digital sovereignty”.

3. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/about-us/who-we-are/contact/profile/cid/christian-bluth-1

4. An agreement between Spain and Portugal aimed at settling conflicts over lands newly discovered by Christopher Columbus and other late 15th-century voyagers.

5. Conference at which the major European powers negotiated and formalized claims to territory in Africa.

6. IDATE, Digiworld 2020 https://en.idate.org/the-digiworld-yearbook-2020-is-available/

7. https://TheOriginalPlatformFund.de/, 2021.

8. EU Commissioner for industrial policy, internal market, digital technology, defence and space.

12. For the Cybersecurity Act and NIS Directive, see https://bit.ly/3gYlE6M

13. For the Digital Services Act and the Digital Market Act, see https://bit.ly/2QIfHR2

14. GAIA-X is a project for the development of a competitive, secure and trustworthy federation of data infrastructure and service providers for Europe, supported by representatives of business, science and administration from Germany and France, together with other European partners. https://bit.ly/3nD241q

15. Customs union, competition rules for the internal market, monetary policy for the euro area, common fisheries policy, common commercial policy, conclusion of international agreements.

16. IDATE, Digiworld 2020, op. cit.

17. European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, https://www.enisa.europa.eu/

References

Hinsley, F.H. (1986). Sovereignty. 2nd edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fischer, J. (2019). ‘The End of the World As We Know It’ Projekt Syndicate. 3 June [online]. Available at: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/us-china-break-europe-by-joschka-fischer-2019-06 (Accessed: 15 June 2021)