A Crucial Decade for European Digital Sovereignty

Abstract: The current decade will be critical for Europe’s aspiration to attain and maintain digital sovereignty so as to effectively protect and promote its humanistic values in the evolving digital ecosystem. Digital sovereignty in the current geopolitical context remains a fluid concept as it must rely on a balanced strategic interdependence with the U.S, China and other global actors. The developing strategy for achieving this relies on the coordinated use of three basic instruments: investment, regulation and completion of the Digital Internal Market. Investment, in addition to the multiannual financial framework (2021-2027) instruments, will draw upon the 20% of the 750 billion Recovery Fund. Regulation, in addition to the Digital Governance Act and the Digital Market Act, will include the Data Act, the new AI regulation and more that is in the pipeline, leveraging the so called “Brussels Effect”. Of key importance for the success of this effort remains the timing and “dovetailing” of the particular actions taken.

It looks increasingly likely that the decade of the 2020’s will be crucial for the future of the economic, political and social impact of digital technologies worldwide.

It will be particularly critical for Europe’s aspiration to attain and maintain digital sovereignty while protecting and promoting cherished values that humanity honed and filtered through 5th century BC Athens and the 18th century AD Enlightenment to our days. Digital sovereignty remains a fluid concept as analysed in Moerel and Timmers (2021). Here, it is not intended to mean digital autarky or absolute autonomy but rather a strategic positioning that ensures a globally balanced inter-dependence where a contestant’s attempt to damage others, risks self-damage.

At the beginning of the last decade, the 2010’s, the digital landscape looked decidedly …rosier. It was still a time of “digital innocence” and great optimism for how, on balance, digital technologies would transform the world.

There was the Arab spring of 2011 and the credible promise that digital technologies in general and the internet and its “social machines” in particular would help to create an informed citizenry that would, in turn, foster and strengthen democracy and social cohesion.

Then came the Snowden revelations and the Cambridge Analytica scandal in 2013, the Brexit referendum and the US elections in 2016 and an avalanche of related developments so that now, at the start of 2021, we are looking at misinformation, conspiracy theories and fake news, turbo-charged by the social media platforms, having circled the globe many times over by the time truth is checked and outed. The 2011 Arab Spring case is now studied as a “Precursor of the Disinformation Age”!

We are also looking at fast evolving, data gobbling, non-transparent AI algorithms which, combined with the business models used by the social media platforms push people to the extremes of the political spectrum, thus emptying the Aristotelian “middle” which is crucial for both democracy and social cohesion.

The rosy digital landscape, and its geopolitical context of the start of the decade of the 2010’s, has been replaced at the start of the 2020’s with a very different one where all kinds of red lights are flashing and warning bells are ringing.

The era of digital innocence and unbridled hope is over, replaced by mitigated belief that the accelerating advances in digital technologies can still be a force for good overall but only provided that governments, industry, academia and individual citizens take actions that can ensure that this belief is realized.

Most of these actions currently proposed and debated are controversial and viewed very differently in the U.S., China, Europe and other parts of the world.

This is at the heart of a complex developing global power play in the context of which Europe is trying to position herself.

Before going further to see how this new decade might play out and why it might well be critical in shaping perhaps several decades that will follow, let us first take a look at the evolving geopolitical context.

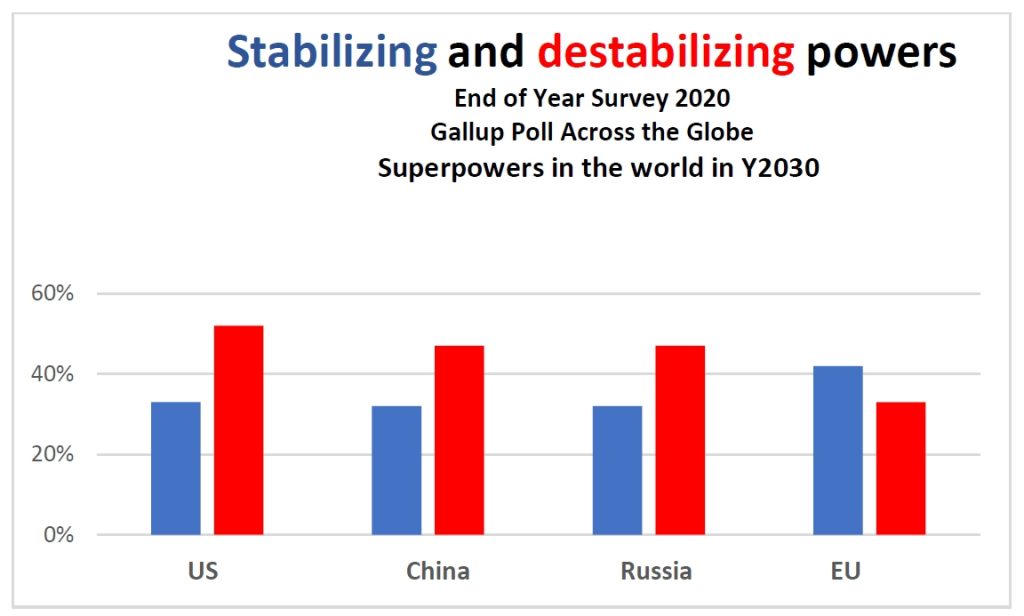

Practically all recent studies conclude the same world superpower array as does the February 2021 Gallup report (Gallup International, 2021) that polled perceptions on this very issue worldwide.

That is, by 2030 there will be two major superpowers combining economic and military prowess that will be jockeying for first place, the US and China.

Quite far behind (further than now) will be the EU closely followed by Russia.

The falling further behind of the EU does not come as a surprise as the EU is not expected to come close to the two big ones without a common foreign and defence policy which, in turn, is not expected to happen during this decade.

But there is an additional finding in the aforementioned Gallup report. The second key question asked (besides which will be the major superpowers by 2030) asked which superpowers would be “stabilizing factors” and which would be destabilizing ones in the world.

The EU is viewed as a stabilizing factor by a higher percentage of people around the globe than either of the two big ones or Russia.

Analysts concur that this perception is strongly correlated with a more general worldwide view of the EU as a non-aggressive soft power.

This also helps explain why EU regulatory initiatives like the GDPR which, despite any putative or real shortcomings, has brought data protection into the public eye, have been rather quickly emulated worldwide by more than 120 countries and therefore why the EU can punch above its geopolitical weight as a soft power with global impact on regulatory issues.

All this has been thoroughly analysed in Anu Bradford’s excellent book “The Brussels effect” (Bradford, 2020) showing that European regulation of the digital landscape has the potential of becoming a blueprint for similar regulation around the world in areas such as data privacy, consumer health and safety, anti-trust and online hate speech.

This, in turn, allows the EU to promote worldwide a European way as an alternative to the libertarian and authoritarian way of shaping the digital ecosystem currently followed in the US and China respectively.

Take the Big Tech oligarchy as an illustration.

It was during the decade of the 2010’s that the GAFAM and their Chinese counterparts have attained their full dominance.

Now, at the start of 2021, we have GAFAM with a 7.6 trillion market value, strengthened during the pandemic and projecting a doubling in sales by the end of the decade.

The economic strength of the giants encourages their bulimic appetite for swallowing small innovators either to integrate them or to bury them. Apple e.g. buys a company every 3 or 4 weeks and has bought over a 100 in the last five years.

First, winner takes all and then size begets size and power begets power.

It was the EU that led the way to create a regulatory framework that would level the playing field and create a more contested digital economy while the US relied on voluntary self-regulation and China on her authoritarian power.

During the last decade, the US has been, to put it mildly, sceptical about such regulation at the time as risking the stifling of innovation but policies are now changing across the Atlantic as well

Anti-competition issues including the possibility of break-ups are now on the table in the US and broader regulatory issues are proposed. Decisions taken (or not taken) there will have crucial impact on how the entire digital ecosystem evolves during the decade of the 2020’s.

The EU and the US remain at odds on a number of digital issues concerning citizen privacy, the related issue of date transfer across the Atlantic and the ongoing spat of how to tax the tech oligarchs.

At the same time, especially after the 2020 US elections, both US and Europe are developing a common concern about China’s use of digital technologies unhindered by ethical, privacy and human rights concerns and the comparative advantage this could give China in leading the race to more and more advanced, data dependent, AI technologies.

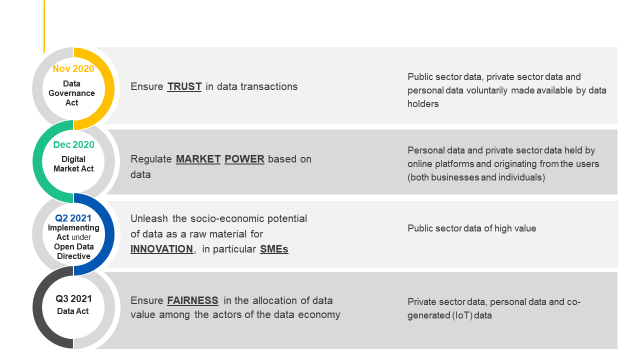

Following the example of GDPR, the EU has proposed or is about to propose an impressive, in scope at least, arsenal of regulatory measures including the AI regulation, Digital services Act, Digital Market Act, Data Governance Act and the Data Act (see also figure 2).

Regulatory global influence constitutes for Europe a necessary, though by no means sufficient step towards attaining and maintaining digital sovereignty.

Regulation complemented with investments and a completed Digital Internal market however does offer a more convincing strategy.

Massive investment in digital infrastructure and technology during this decade is now visible. The 150 billion euros comprising the 20% of the pandemic triggered 750 billion Recovery Fund is expected to leverage much greater investments via the European Investment Bank and other institutions as well as both public and private investments at the national level. As an illustration, a European federated, next-generation cloud service, building on the experience of GAIA-X, would be a top investment priority during the first half of the current decade. Additional planned investments would go towards doubling the EU share of global semiconductor production by 2030, universal EU 5G coverage and quantum computing.

In parallel, completion of the European Digital Internal Market would enable European digital companies to look at continent-wide opportunities with 450 million potential clients as a first step towards becoming competitive global players.

It is now recognized at the highest political decision making level that European Digital Sovereignty is “central to European Sovereignty” and is “the capability that Europe must have to make its own choices, based on its own values, respecting its own rules” (quotes by the Presidents of the Council and the Commission respectively)

At the same time, European Digital Sovereignty is necessary for empowering Europe to help ensure a digital transformation which is inspired, as stated in the Treaty on European Union, by “the humanist inheritance of Europe, from which we have developed the universal values of the inviolable and inalienable rights of the human person, freedom, democracy, equality and the rule of law” (Ministerial Council of the EU, 2020)

During the current decade, every step taken towards European Digital Sovereignty will be unavoidably interacting with the EU’s geopolitical positioning with respect to other global players and the positioning of China and the US in particular.

Just as an illustration, China announced in early March 2021 the launch of a five-year program aimed to decrease China’s technological dependency on the West in thirty areas deemed of specific importance such as microprocessors, O.S. for mobiles and aircraft design software. This comes, to a large extent, as a reaction to the steps taken by the US in the last four years to curtail the power of Chinese tech giants like Huawei and SMI.

A week before the Chinese move, the Biden government in the US has announced steps to decrease the dependency of the US on rare earths and other imports affecting the digital supply chain.

Europe’s ability to attain and maintain digital sovereignty during such continuous rebalancing of strategic interdependence among the global players expected during the 20’s will depend on how quickly and effectively it acts and reacts in such a dynamic geopolitical context.

In some cases, selective European autarchy may be the right move, while in others trusted alliances may be the best option. There may also be cases where planning to leapfrog to the next generation of technology may be preferable rather than trying to catch up on applications of current ones.

Quick decisions and follow-up steps are not easy for the European Union, an incomplete construct of 27 small, in the global context, countries that do not have a common foreign and defence policy which can provide a tool to help face China’s state supported industrial policy and the defence procurement innovation pull of the US.

This presents a real challenge for the European Sovereignty during this decade.

To counter this inherent handicap, in some strategically selected cases, a subset of some EU countries could potentially move forward together quickly in a particular technology area where they are very advanced (e.g. quantum computing) with the possibility left open that other fellow member states could join later.

Perhaps selected quick, decisive moves during this decade in Europe could be more effective than the unavoidably slow process of attempting to tease out a full industrial policy equivalent first.

A truly unhindered Digital Internal Market, regulation and investments are actions that constitute powerful building blocks of a potentially effective Digital Sovereignty strategy for Europe.

Part of this strategy is the timing of new regulation and new investment in a particular area so that this investment and the players involved can draw maximum benefit as the regulation’s “first users”.

This is why the timeline of impact, the dynamic dovetailing of the specific actions emanating from aforementioned building blocks so as maximize the added value resulting from combining them in a timely and effective fashion while dynamically factoring in developments in the geopolitical context, will be of “make or break” significance during the decade.

Success for this strategy complemented by the continued nurturing of humanistic values and leaders that embrace them would make the 2020’s a very good decade for Europe.

References

Moerel, L., Timmers, P. (2021). Reflections on Digital Sovereignty, EU CYBER DIRECT, January 2021.

Gallup International. (2021). Superpowers in the World in Y2030. February 2021.

Bradford, Anu. (2020). The Brussels Effect, Oxford University Press.

DigHumTUWien. (2021). Preventing Data Colonialism without resorting to protectionism – The European strategy [Online video]. 23 February 2020. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O7tSwB_3a1w (Accessed: 9 June 2021).

Ministerial Council of the EU. (2020). Berlin Declaration on Digital Society and Value-based Digital Government at the ministerial meeting during the German Presidency of the Council of the European Union on 8 December 2020. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/newsroom/dae/document.cfm?doc_id=75984 (Accessed: 3 May 2021)